Incidents rarely start with “bad data”

A common misconception is that data incidents result from incorrect or fraudulent information. In practice, many incidents involve accurate data that was used inappropriately, reused without review, or interpreted outside its original context.

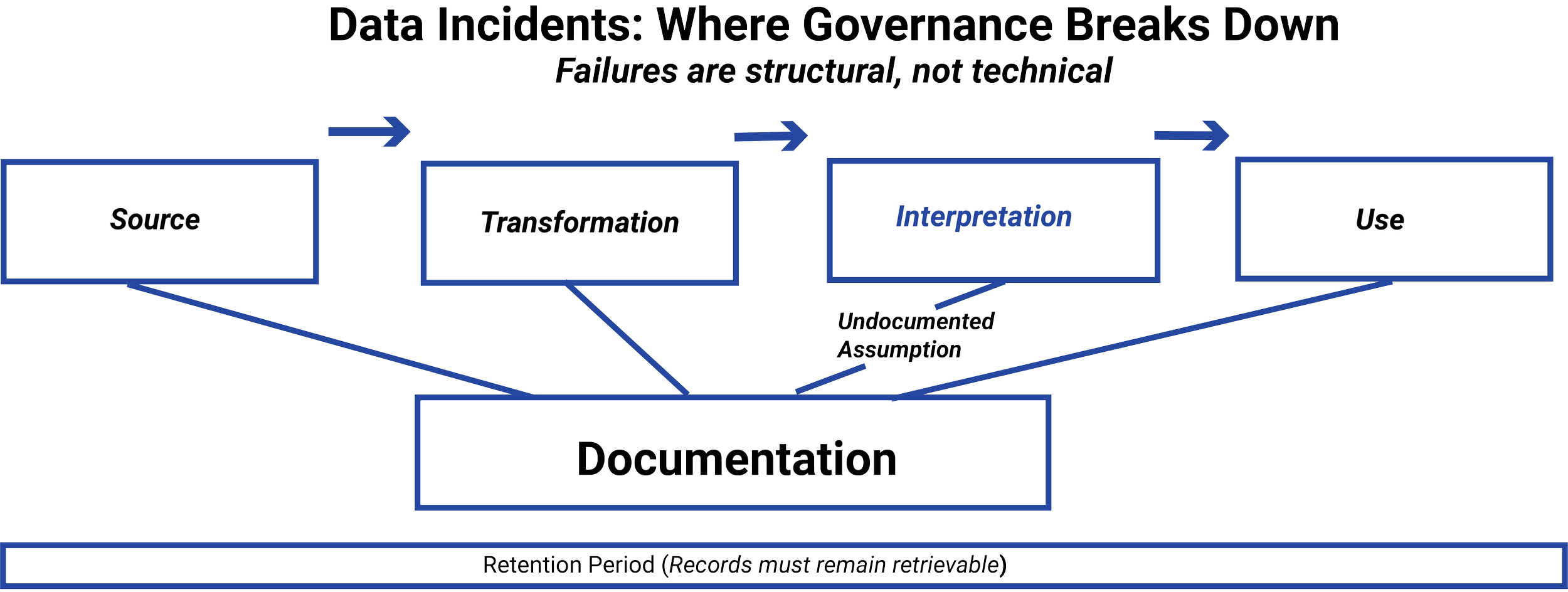

Data collected for one purpose may later be repurposed informally. Derived outputs may be treated as objective facts. Internal analyses may migrate into client-facing materials without adequate review. In each case, the underlying data may be sound, but governance breaks down as meaning accumulates.

Regulators focus on these breakdowns, not just on factual accuracy.

Common patterns regulators identify

While incidents vary, regulators frequently observe similar structural weaknesses.

One pattern is informal reuse, where data is repurposed across teams without reassessing permissions, assumptions, or limitations. Another is documentation gaps, where key interpretive decisions aren’t recorded, leaving firms unable to explain how outcomes were produced.

A third pattern involves diffuse accountability, where no single role or function can clearly explain or defend how data was used. When responsibility is spread across systems or teams, supervision becomes ineffective.

These patterns tend to coexist rather than occur in isolation.

Why issues are discovered late

Many data incidents are identified downstream, only after outputs reach clients, markets, or regulators. This isn’t because firms lack controls entirely, but because those controls are often concentrated downstream.

When governance focuses primarily on final communications or products, earlier data decisions may escape review. By the time an issue is detected, data may already have been reused, transformed, or embedded in multiple workflows.

Regulators view late discovery as evidence that governance was reactive rather than preventive.

Most data-related regulatory incidents don’t begin with malicious intent or technical failure. They begin with reasonable decisions made without sufficient governance, documentation, or supervision.

Regulators study these incidents, not to punish innovation, but to understand where control frameworks failed. This lesson examines common data incident patterns and explains why issues are often discovered only after data has already influenced decisions or communications.

IN THIS LESSON

What regulators expect firms to learn from incidents

Regulators don’t expect firms to eliminate all data-related risk. They do expect firms to learn systematically from incidents and to strengthen controls accordingly.

This includes identifying where governance failed, updating documentation and supervision practices, and preventing similar issues from recurring. Firms that treat incidents as isolated errors often face repeat findings. Firms that treat them as governance signals are viewed more favorably.

The emphasis is on improvement, not perfection.

Why this matters before analytics or AI

Analytics and AI systems amplify the consequences of weak governance. When similar incidents occur in automated or scaled environments, their impact can be broader and harder to contain.

Regulators increasingly expect firms to demonstrate that they have addressed historical data governance weaknesses before deploying advanced tools. Incidents that occurred in manual or simple workflows are often viewed as warnings, not exceptions.

Learning from past failures is, therefore, a prerequisite for responsible automation.

Additional Resources

-

UK Information Commissioner’s Office — Accountability and Auditability in Automated Systems

Discusses why retention of decision context (including inputs and configuration) is critical where automated tools influence outcomes.Industry Commentary on Audit Replay for AI and Analytics

Explores how replay shifts from reproducing outputs to reconstructing decision conditions in probabilistic or evolving systems.Academic Literature on Traceability in Automated Decision Systems

Examines the distinction between outcome replication and decision reconstruction, reinforcing why replay focuses on context rather than determinism.

-

COSO — Internal Control Framework (Control Failures and Root Cause Analysis)

Emphasizes that incidents often reflect breakdowns in control design or execution, particularly where decisions are undocumented or responsibility is diffuse.Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Guidance on Incident Analysis

Encourages firms to treat incidents as signals of systemic weaknesses rather than isolated errors, aligning with regulators’ focus on pattern recognition.Basel Committee on Banking Supervision — Governance Lessons from Operational Failures

Highlights how incremental, well-intentioned decisions can accumulate into material governance failures when oversight does not keep pace with complexity.

-

NIST — Data Governance and Risk Management Concepts

Frames inappropriate reuse and undocumented transformation as accountability failures rather than technical defects.OECD — Accountability and Transparency Principles

Reinforce that organizations must be able to explain how data was used and interpreted, especially when outcomes adversely affect clients or markets.Model Risk Management Commentary (SR 11-7 Legacy Framework)

Introduced the expectation that interpretive choices embedded in models and analytics be documented, reviewed, and owned — lessons now applied beyond quantitative models.

-

UK Information Commissioner’s Office — Case Studies on Data Misuse and Secondary Use

Illustrate how accurate data can still create regulatory exposure when reused outside its original context.Industry Commentary on “Data as Liability”

Explores why firms with large, lightly governed data environments experience more frequent and severe incidents.Academic Literature on Organizational Failures and Latent Risk

Examines how small governance gaps compound over time, leading to incidents that appear sudden but were structurally inevitable.