Bias begins before modeling

Bias is commonly associated with algorithms or models, but it frequently enters the process before any modeling occurs. Choices about which data to collect, which observations to exclude, and how categories are defined all influence outcomes.

Even well-established datasets reflect historical conditions, institutional preferences, and operational constraints. When those datasets are reused without context, they can embed assumptions that are no longer valid or appropriate for the current use case.

From a regulatory perspective, bias isn’t limited to intent. It includes structural and historical effects that shape outcomes, regardless of whether they’re recognized.

Sampling error as a governance issue

Sampling error is often treated as a statistical concern, but in regulated environments, it also represents a governance issue. Small or unrepresentative samples can produce results that appear meaningful while masking uncertainty or instability.

When such results inform decisions, segmentation, or communication, firms may inadvertently overstate confidence or precision. Regulators are less concerned with whether a calculation is technically correct than with whether its limitations are understood, documented, and communicated appropriately.

Failure to recognize sampling limitations can therefore create both analytical and compliance risk.

Model risk exists without complex models

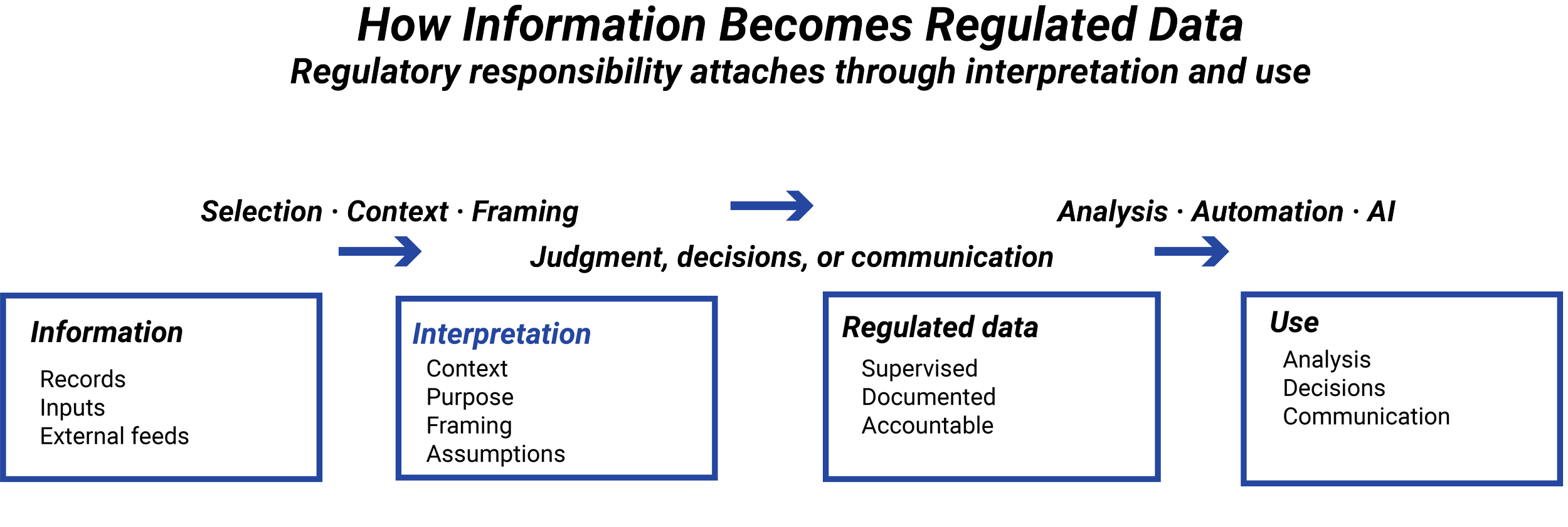

Model risk isn’t limited to sophisticated quantitative systems. Any process that transforms data into outputs using assumptions, rules, or logic introduces model risk.

This includes scoring frameworks, classification rules, thresholds, and even simple rankings or summaries. When these mechanisms are treated as neutral or mechanical, their assumptions may go unexamined, and their outputs may be trusted more than warranted.

Regulators expect firms to understand the limits of such processes and to avoid presenting derived outputs as definitive or objective when they are not.

Data-driven decisions often carry an aura of objectivity. Numbers feel precise, models feel disciplined, and outputs feel defensible. In regulated finance, that confidence can be misleading.

Bias, sampling error, and model risk don’t originate in advanced analytics or artificial intelligence. They’re often introduced much earlier, through how datasets are assembled, interpreted, and reused. This lesson explains why these risks exist even in simple analyses and why regulators expect firms to account for them explicitly.

IN THIS LESSON

Why regulators care about these risks

Regulators focus on bias, sampling error, and model risk because they affect fairness, suitability, and accuracy. When data-driven outputs influence client outcomes or public communications, unexamined assumptions can lead to misleading conclusions or inappropriate actions.

Importantly, regulators don’t require firms to eliminate these risks entirely. They require firms to recognize, manage, and document them. Transparency about limitations is often more important than technical sophistication.

Why this matters before analytics or AI

Analytics and AI systems amplify the impact of bias, sampling error, and model risk by applying them at speed and scale. If these risks aren’t addressed early (at the data level), automation can propagate them widely and consistently.

Establishing awareness and governance around data issues before introducing advanced tools allows firms to deploy analytics responsibly. Proper documentation also provides a defensible framework for explaining limitations when regulators or stakeholders ask how outputs were produced.

Additional Resources

-

SEC — Division of Examinations Risk Alerts (Analytics, Conflicts, and AI)

Examination materials highlight concerns where data-driven systems embed bias, amplify assumptions, or rely on incomplete or unrepresentative samples that affect investor outcomes or communications.SEC — Predictive Data and Digital Engagement Practices Commentary

Addresses risks associated with using predictive signals and behavioral data, emphasizing that bias and model assumptions can materially affect suitability and fairness.FINRA — Supervision of Analytics and Targeted Communications

FINRA guidance and enforcement history reflect heightened scrutiny where data-driven segmentation, scoring, or ranking introduces bias or misleading implications.

-

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency — Model Risk Management (SR 11-7)

Establishes supervisory expectations for identifying, documenting, and managing model assumptions, limitations, and potential bias arising from data inputs and transformations.Federal Reserve Board — Supervisory Guidance on Fair Lending and Model Governance

Reinforces that sampling choices and proxy variables can introduce bias, requiring governance and review even when models are statistically sound.

-

National Institute of Standards and Technology — AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF)

Identifies data bias, representativeness, and transformation risk as foundational contributors to downstream model and decision risk.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development — Principles on AI and Data Governance

Emphasizes accountability for biased or harmful outcomes arising from data-driven systems, regardless of intent or technical sophistication.

-

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision — Model Governance and Risk Aggregation Principles

Reinforces that data quality, representativeness, and transformation directly affect risk measurement and governance effectiveness.Academic Literature — Bias and Sampling in Financial Models

Widely documents how technically valid models can produce systematically skewed outcomes due to data selection and preprocessing choices.