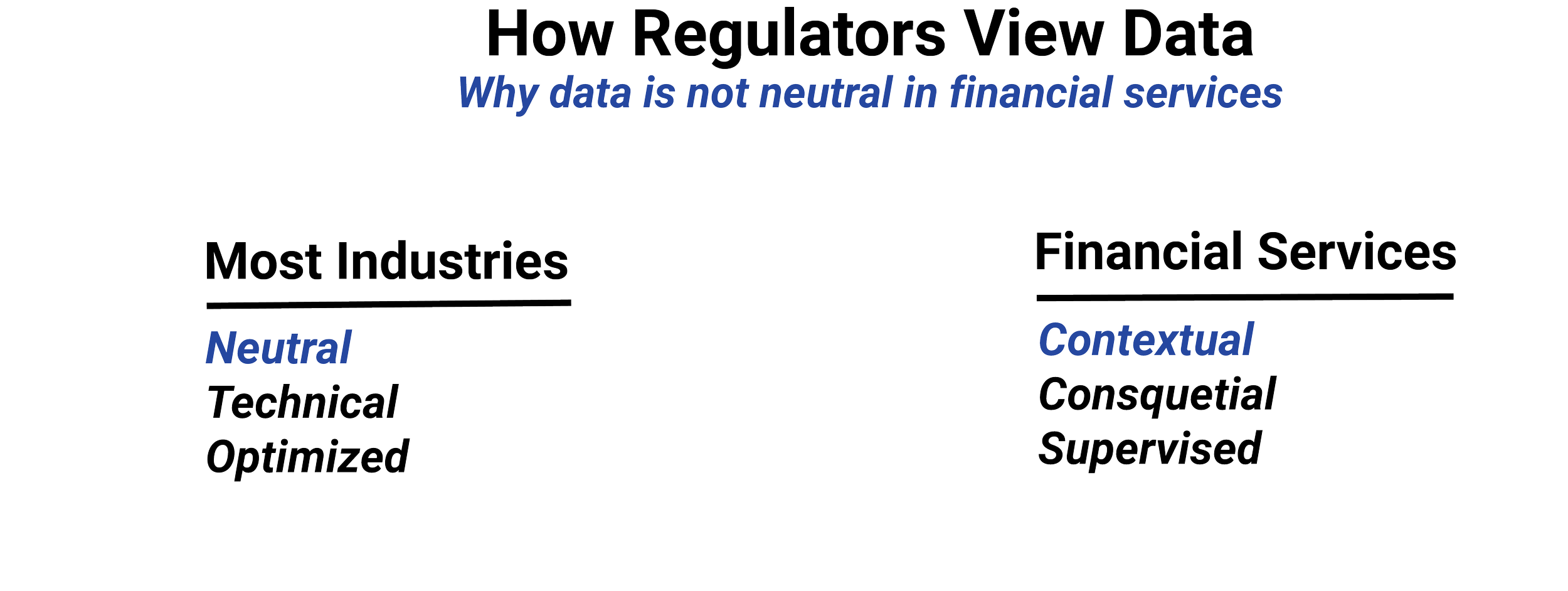

Not all data carries the same regulatory weight.

Two datasets may look similar in a dashboard or model, but trigger very different supervisory, documentation, and suitability obligations. Those differences don’t come from how sophisticated the analysis is. They come from what the data represents and how it’s created.

This lesson introduces three broad categories of data used in financial organizations: common, alternative, and derived. It also explains why risk increases as data moves between them.

Understanding these distinctions is essential before introducing analytics, automation, or AI. Governance decisions depend on them.

IN THIS LESSON

Common data

As the term implies, common data is information that’s widely used, well understood, and historically accepted within regulated financial activity.

Examples include market prices, security identifiers, issuer fundamentals, economic indicators, and standardized client account information. It’s typically sourced from established providers or internal systems built for regulatory compliance.

Because common data is familiar, it’s often treated as low risk. That assumption is only partially correct. It still carries obligations around accuracy, timeliness, suitability, and use. However, the regulatory expectations around it are generally clearer, and supervisory frameworks are more mature.

The key point is not that common data is “safe,” but that its risks are known and legible. Proper disclosure of the source of the data in public-facing material is generally understood.

Alternative data

Alternative data includes information that falls outside traditional financial datasets but is used to generate insights, signals, or classifications.

This can include transactional metadata, geolocation patterns, web activity, satellite imagery, sentiment indicators, or aggregated behavioral signals. The defining feature is not novelty, but contextual ambiguity.

Alternative data often raises questions that regulators care deeply about:

Why does this data exist?

How was it collected?

What permissions govern its use?

What assumptions are embedded in it?

Even when alternative data is aggregated or anonymized, its interpretation can introduce bias, privacy risk, or suitability concerns. These risks are often less obvious than with common data, which makes them harder to supervise.

The moment alternative data is used to inform decisions, segmentation, prioritization, or recommendations, it becomes a governance issue—regardless of whether it’s client-facing.

Derived data

Derived data is created when existing data is transformed, combined, summarized, scored, labeled, or inferred.

This includes rankings, risk scores, client segments, propensity indicators, summaries, classifications, and model outputs. Derived data doesn’t exist independently. It reflects the assumptions, logic, and objectives embedded in its creation.

From a regulatory perspective, derived data is often where risk concentrates. Even when inputs are permitted and well understood, derivation introduces:

New meaning

New potential for error

New documentation obligations

New supervisory responsibility

Importantly, derived data may appear objective or technical while still encoding judgment. That judgment must be explainable.

Why does risk increase as data moves downstream?

As data moves from common to alternative to derived forms, three things tend to happen simultaneously.

First, interpretive distance increases. The further the data moves from its original source, the harder it becomes to explain what it truly represents.

Second, accountability becomes less obvious. Responsibility can become diffused across systems, teams, or vendors.

Third, documentation gaps emerge. Transformations that feel routine are often poorly recorded, even though they materially affect outcomes.

This is why regulators focus not just on original data sources, but on how data is transformed and reused over time.

A simple rule for governance

A useful mental model is this:

The more interpretation a dataset contains, the more governance it requires.

Common data generally requires baseline controls.

Alternative data requires contextual review and justification.

Derived data requires explicit documentation, supervision, and explainability.

This rule applies regardless of whether AI is involved.

Let’s consider an example. A dataset may begin as common data, such as standard client account and transaction records used for reporting or operations. When that same data is combined with additional signals or contextual indicators to identify patterns or segments of interest, it functions as alternative data, reflecting interpretive choices about relevance and purpose. If those signals are then transformed into outputs such as rankings, scores, or prioritization lists that guide decisions or communications, the result is derived data.

While the underlying information may remain familiar, each step embeds additional meaning and judgment. As a result, interpretive distance increases, accountability becomes less obvious, and documentation requirements escalate—illustrating why regulatory risk rises as data moves from common to alternative to derived forms.

Why this matters before analytics or AI

Analytics and AI accelerate the use of derived data.

If a firm does not clearly understand which data is common, which is alternative, and which is derived, it cannot reliably assess risk, assign accountability, or respond to regulatory questions.

Most AI-related incidents trace back to poorly governed derived data—not exotic models.

This lesson is about recognizing where meaning changes, not about restricting innovation.

Additional Resources

-

SEC — Marketing Rule (Rule 206(4)-1) Interpretive Commentary

Reinforces that risk is evaluated based on how information is used and transformed, not whether the underlying data is traditional or alternative.FINRA — Rule 2210: Communications with the Public (Conceptual Application)

Establishes that derived classifications, rankings, and segments used in communications carry greater supervisory risk than raw inputs.SEC — Division of Examinations Risk Alerts (Data Analytics, AI, Conflicts)

Exam risk alerts consistently emphasize how data is sourced, transformed, and reused, with heightened scrutiny as analytics become more interpretive.

-

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency — Model Risk Management (SR 11-7)

Introduced the principle that acceptable inputs can produce higher-risk outputs through transformation, forming the conceptual basis for derived data risk.Federal Reserve Board — Supervisory Guidance on Modeling and Stress Testing

Distinguishes between raw data, alternative signals, and derived outputs, applying escalating governance expectations as interpretation increases.

-

European Data Protection Board — Purpose Limitation and Derived Data Guidance

Recognizes that inferred and derived data may carry greater sensitivity and accountability obligations than original source data.Information Commissioner's Office — Guidance on AI, Profiling, and Inferred Data

Explicitly differentiates between observed, inferred, and predicted data, reinforcing the regulatory relevance of data transformation stages.

-

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision — Principles for Risk Data Aggregation and Reporting

Emphasizes that data transformations introduce new governance obligations, even when underlying inputs are well controlled.Institutional Asset Management Literature — Origins of “Alternative Data”

The concept of alternative data emerged in quantitative investing and hedge funds, with regulatory frameworks later adapting to its interpretive risks.